Veterans Day Reflections: Honoring Veterans, Resisting War, and Longing For Peace

Veterans Day is a complicated holiday for me.

I grew up fairly single-minded in my appreciation for veterans and the U.S. military. I grew up under 9/11 rhetoric and the Homeland Security Advisory System; militarism and reverence for soldiers was in the water, and I’m ashamed to say that this sacred patriotic admiration was carried alongside my faith in Jesus in some unholy admixture of Christ and Caesar. To my young mind, ours was the one nation under God, in whom all true Americans trust, and the bravery exhibited on the battlefield was nothing less than godly doxology.

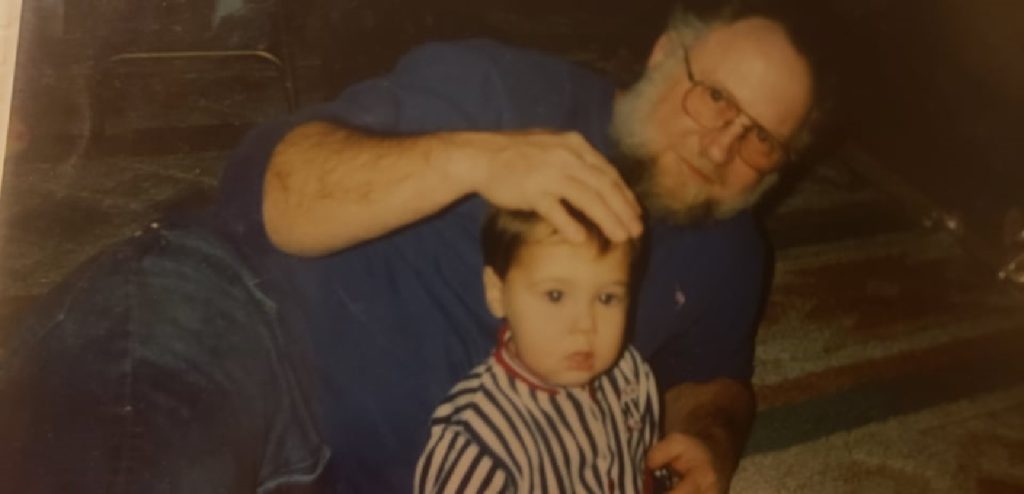

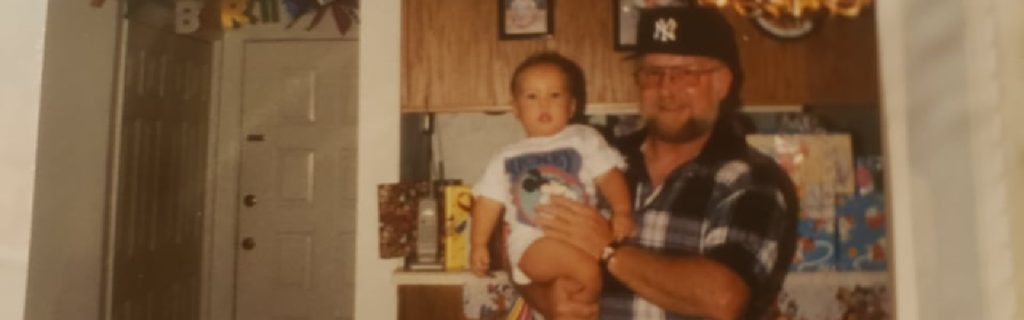

Like many Americans, I am related to several veterans. Two of my uncles were deployed in the Iraq war, my grandfather fought in Vietnam, and my father would have served in the National Guard had he not been medically discharged shortly before I was born for complications resulting from a club foot. So it was altogether confusing, awkward, and in some ways painful when I found myself turning strict pacifist in my high school years.

But this is not a post about pacifism. It is about Veterans Day and how I celebrate it.

I used to observe Veterans Day in ways that were intentionally offensive, divisive, and instigative, mostly through social media posts and starting arguments with classmates. I wanted – with no awareness of the deep irony – to pick a fight. But now that I’ve grown up a little, and especially now that I’ve had kids, I want to observe Veterans Day in a way that is deeper and more reverent of the sacred dignity borne by the men and women who have suffered and fought for this country. Don’t get me wrong. I am still a committed advocate of Christocentric nonviolence (despite the several promises from well-meaning individuals that I would change my mind when I had children), but as I consider the veterans in my life, especially my grandfather, I feel it in my bones that their experience cannot go ignored, dismissed, or trivialized.

I am not talking about celebrating war, bloodshed, and militarism. Since its inception, the United States has made a habit of waging wars to expand its imperial power in the world (the War of 1812, the Black Hills War, the Philippine-American war, and the Mexican American War to name only a few). U.S. military forces have been used to steal lands, seize resources, and install oppressive dictators. It is not uncommon to hear stories of torture, civilian targeting, rape, and massacre. This is not a plea to celebrate the Eddie Gallaghers and the Nicholas Slattens, who will nonetheless be thanked and applauded on today and every other day by their supporters.

What I’m talking about is refusing the militaristic narrative that renders them deployable and commendable but expendable, caring for veterans in a way that goes far beyond and far deeper than gratitude.

While growing up, I never really talked to my grandfather about Vietnam. He would sometimes – and very infrequently – make passing reference to his time in the war, complain about the jungle, and tell the story about a guy who wanted to get discharged for “bad dreams”. But there was always a look in his eye and voice behind his voice that warned me that bad things happened, that he did bad things, and it wasn’t something he really wanted to talk about.

Even though he’s never told me this, I know that my grandfather has killed people. I know that he has nightmares about it. I know the PTSD and the pain lingering from his time in the jungles and the swamps are with him every day. I know that he joined the military because poverty and impoverished parenting in a society with few safety nets and support networks left him with little or no choice. I know that he lost friends and pieces of himself and I know that he wishes none of it had happened the way that it did.

It makes me think of the soldiers who died and the many who survived but suffered in World War I, that Great War to End All Wars, and the string of unofficial ceasefires along the Western Front that rose out of a recognition that they were fighting, dying, and killing for nothing. It makes me think of the Afghanistan Papers and the other reminders that often – all too often – soldiers are pawns in a P.R. game for politicians and high ranking officials. It makes me think of the near twenty veterans who kill themselves every day, presumably not merely from a lack of appreciation, so that by now nearly four times as many troops and veterans have died by suicide than in combat. But we wave our flags and send our children uncritically off to die in the name of God and country, and the ones who make it come back in pieces.

In light of all of this, how can we observe Veterans Day? How do I do so in a way that serves the humanity, dignity, and Image of God borne by my grandfather?

It has been a very long time since I have thanked a Veteran for their service, and as a Christian, I cannot and will not celebrate war. But Veterans Day didn’t start as a day to celebrate war; it started as Armistice Day, established November 11, 1919, to commemorate the end of hostilities – what was meant to be the permanent end of hostilities – in World War I, purportedly the world’s final war. It was a day to remember the pain, suffering, loss, and death of war, and to let that grief create in us not bloodlust but a longing for peace.

So for Veterans Day, and in honor of my grandfather and the many other veterans who have suffered for causes long dismissed as unnecessary, those who hunger and thirst for righteousness and peace should resist war and violence. Even those of us who did not find in Scripture a clear call for nonviolence must resist war and violence and reject any ethic that would call us to unquestioningly sacrifice our children to Molech by any other name. We must restore the conviction long held in the Christian tradition that even if violence is necessary it is still our last resort. We should not rush to arms, to vengeance, to shows of power and might, for if it is the meek that inherit the earth then power and might are not worth dying for, and they are certainly not worth killing for.

You don’t have to be a pacifist to know that war breaks people, not least the soldiers. Erich Maria Remarque, having served his own time, describes war as a place of knowing “nothing of life but despair, death, fear, and fatuous superficiality cast over an abyss of sorrow” and seeing “how peoples are set against one another, and in silence, unknowingly, foolishly, obediently, innocently slay one another” (All Quiet on the Western Front). So you don’t have to be a pacifist to know that it was never meant to be this way.

If we must have violence, let it not be needless, careless, and senseless. Let us hold accountable those who commit atrocities in war and those who use human beings as pawns in their own games to their own ends. Let us confess the suffering caused by our military forces and lament the ways in which war has broken, bent, and robbed our veterans of life and flourishing, often for causes less noble than the ones touted by purveyors of bloodshed. Let us listen to the voices of veterans who are calling out for help, for healing, and for forgiveness, and let us offer that to them where we can. And if Christians we are, whether we be pacifists or just war theorists, let us hunger for the world to come and pursue tirelessly the things which make for peace.

This is how we serve the humanity, dignity, and Image of God borne by those who, like my grandfather, have been dehumanized by militarism, imperialism, and violence, not by pretending that all their causes were just, but by telling the truth about the ways that they have been used and abused by the powers that be. We honor them by fighting the beast which chewed them up and spit them out.

So on Veterans Day and on every day you can, listen to the stories of suffering, heartache, loss, and pain the veterans in your life have to share. Learn about the horrid things that have been done to them – and the horrid things that they have been used to accomplish – and mourn with them and go with them to the throne of the Prince of Peace. Be patient with their angers, their frustrations, and even their hatreds. In the ways that they have disassociated from themselves and others, help them to reconnect with their God, their communities, and their humanity. Welcome them in, love them, and bear their burdens with them. Tell better stories of the beginning and the end of the world, stories that affirm that human beings were not made to slaughter and be slaughtered. Let our church be a community that facilitates regular confession, repentance, and forgiveness, for all our hands are bloodied, and let us together find creative ways to beat our swords into ploughshares, spears into fish hooks, and practice war no more.