Surrounded by Swords

Doing Theology as an American-Made Mestizo, Pt. 2

The following is the second part of a series reflecting on a Mixed-Heritage Filipino-American Identity in honor of Fil-Am Heritage Month. You can find part one here.

I will be discussing things like Filipino Invisibility, liminality and in-betweenness, tokenism, and the history of Filipino Diaspora. Some of the experiences will be common to radicalized communities, others will be particular to mixed-heritage persons, and others will be specific to me and my family. Ultimately, what I am building toward is a life-long struggle of theological reflection on mixed-heritage experience. Isang Bagsak.

She was old enough to need a walker and talk like the creaking of rocking chair, but she was sweet and genuinely curious about what my fellow students were working on in the Edwards Mill at College of the Ozarks. Ours was a tourist-centered work-study. We wove baskets, loomed rugs and blankets, and milled flour and grits. Her questions were typical—your major, where you’re from, do you like going to school here, that sort of thing, questions whose answers we were practiced in giving with great exaggeration.

One by one, she shuffled along and express her admiration at such hardworking youths. She reminded me of my great-grandmother, who had passed away not a year prior, so I was—for once—genuinely excited to speak to a tourist. But when she came to me, she stopped her shuffling and stared for a moment too long before asking, “And you, are you from here, or Japan?”

The room got dead quiet as she straightened herself up and glared me down. “I’m not from Missouri, no, but I was born and raised in Arkansas.”

Her gaze unmoving, she replied quickly, “Well, I think I’ll be leaving now, thank you.”

She turned and, without another word, left the building with a scowl on her face. A few nervous laughs while some left for the break room to escape the tension. It was neither my first nor last encounter with racism, but it was the first time someone had ever looked at me with such palpable disdain for my heritage.

I shared the story with some other students, who met with several strategies for explaining away the racism. Perhaps she was just embarrassed that she guessed my hometown wrong. Or maybe she realized she was late for something and I and everyone else just mistook her urgency for malice. But my favorite response went something like this: That sucks, but you have to understand that she lived through World War II, so she’s probably got some valid reasons to dislike Japanese people.

“But, I’m not Japanese,” I’d say.

“Oh, but she doesn’t know that, so maybe show her some grace.”

Despite the long history of troubled US-Philippine relations, Americans are largely ignorant to the history and lingering impacts of American colonial aspirations in the pacific. Fil-Ams carry these stories and struggles with them while others benefit from a chronically short historical memory. So, when an old racist with a walker tells me that my presence is unwelcome, it does not matter that she misidentifies and misremembers. All that matters is that her anxieties are comforted.

But unless we are willing to throw out the Old Testament (and, admittedly, Christians aren’t well-known for appreciation of the Old Testament), we are forced to admit that histories and struggles matter to the formation of peoples and persons. It matters to the formation of Americans as much as it matters to Filipinos and Fil-Ams. It matters to the formation and theological contributions of the churches in America and in the Philippines. And it matters to my career as a theologian.

A Brief History of a Long Oppression

Spanish Colonialism

The Philippines are a string of roughly 7,000 islands that were originally inhabitted, as they are today, by a multiplicity of tribes with impressive intercommunal systems of mutual benefit and collaboration. These were clans with developed political, economic, and military aspirations, connected to the outside world through extensive trade and the exchange of goods and ideas alike. A far cry from the “barbarians” Miguel de Legazpi described, Ferdinand Magellan arrived in 1521 to find diverse, dynamic societies well-versed in shipbuilding, metallurgy, pottery, weaving, weaponry, construction, and artistry.

Magellan’s expedition was, by most accounts, an utter failure. Despite being commonly miscredited with circumnavigating the globe, Magellan’s journey meets a bloodly end just over a month after making landfall in the Philippines. Consumed by delusions of conquest, wealth, and glory, Magellan engaged Datu LapuLapu (a Filipino chieftan), but was outwit, humiliated, and killed, along with most of his men. When all was said and done, the fleeing Iberians limped home withonly one of the five original ships and a mere 18 of the original 260 men.

But the Spaniards would have nothing of resistance or native autonomy, and four subsequent expeditions led to the eventual subjugation of the Philippines under Spanish colonial rule with the capture of Maynila on June 3, 1572. Not only did the Catholic church bless the conquest, but it also provided a theological framework for justifying and implementing the oppression. For the next three centuries, Filipinos were subject to constant exploitation, abuse, rape, slavery, brutality, and injustice of every kind, the price to pay for civilization and the cross.

But Spain could not maintain their dominance forever. Through the resolute actions of Filipinos like Jose Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, Emilio Aguinaldo, Marcelo H. Del Pilar, and Apolinario Mabini (among many others), the Philippines were able to gain control of the strategic island of Luzon and declare their independence, establishing the first Asian government based on a democratically developed constitution.

Alas, the way of empire is never keen to respect the sovereignty of indigenous peoples. So, in 1898, Spain sold to the United States the islands that were no longer—and were never—theirs to sell, marking the end of one war (the Spanish-American War) and the beginning of another.

American Colonialism

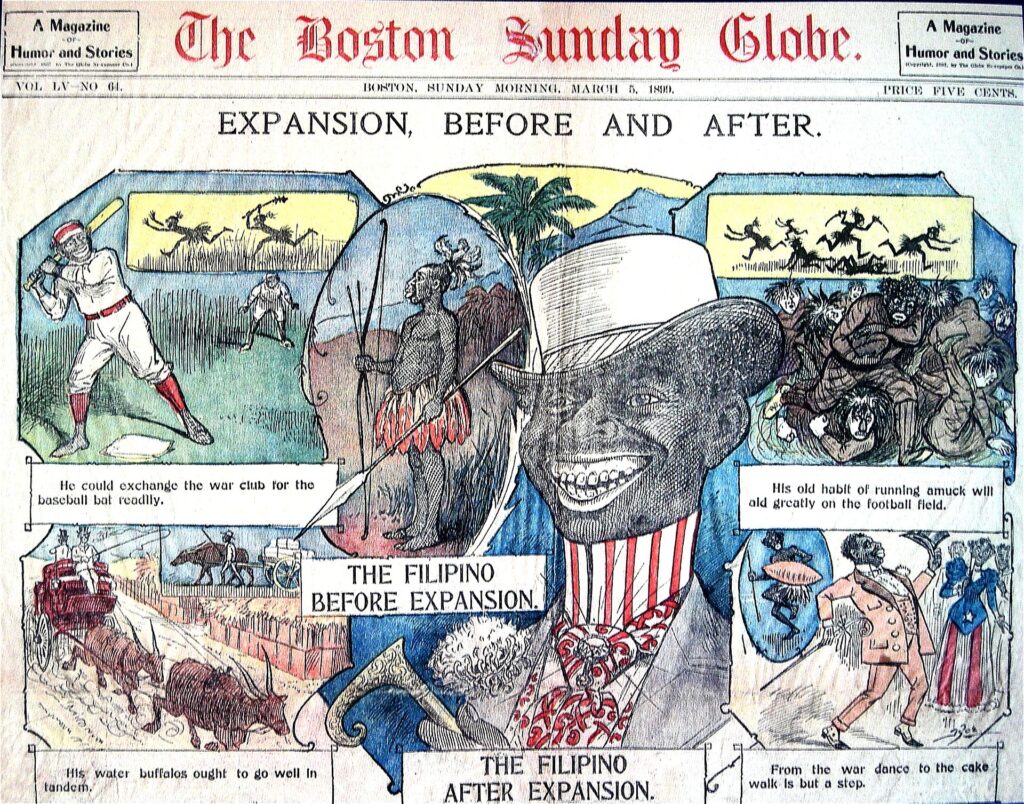

The Philippine-American War (the “Forgotten War”) lasted three years (1899-1902). In response to continued resistance efforts in both the Philippines and the United States, President William McKinley advanced the idea of Benevolent Assimilation on the claim that, through prayer, he had come to realize that the Filipinos were unfit, uncivilized, and in need of parental discipline baptized in the blood of Christ. Republican Senator Albert Beveridge of Indiana called the island inhabitants people of “savage blood”, noting that one “must never forget that in dealing with the Filipinos we deal with children.”

Massive propaganda campaigns ensued, culminating in the 1904 “Philippine Reservation” at the St. Louis World’s Fair. The U.S. captured and imported over a thousand Filipinos and detained them in the largest human zoo in recorded history, so that Caucasians could come and see first-hand the savages and their need for American benevolence.

By 1913, American military occupation had resulted in the deaths of an estimated one and a half million Filipinos. In an act of particular (though not unique) cruelty, General Jacob Smith—renowned for his misconduct during the Civil War—issued the famous “Kill Everyone Over Ten” order. His soldiers marched through the islands, killing thousands.

For this and more, the Americans atoned with schools, teachers, military basis, and foreign exchange programs aimed at turning the Philippines into an oriental version of the American Dream. This well-oiled, well-funded, well-planned system of colonialism resulted in a reality where a majority of Filipinos came to believe that they were lesser humans, accepting white supremacy and American elitism. The US, reaching maturity as an imperial superpower, drew heavily on its new colony to supply cheap labor for its Hawaiian sugar fields, Alaskan fisheries, and California farms.

These “little brown monkeys” would find an unwelcoming America, only to be hunted, beaten, dragged by horse, hung, and murdered. The most memorable—and yet, largely forgotten—incident was the 1930 Watsonville Riots, when hundreds of white vigilantes attacked Filipino dance clubs and roamed the streets for days, beating and shooting on sight.

Neocolonialism

The US, like the Spanish before them, did not recognize the humanity of the Filipinos. However, the independence of the Philippines—established in 1898 by natives—was finally (and begrudgingly) recognized on July 4th, 1946. Upon recognition, America refused the promised benefits to most Filipinos who had fought alongside US citizens in World War II, a petty slight for losing their colony. A small price to pay for freedom by a people who had already paid too much.

However, the effects of colonialism continue to haunt the islands and its descendants. Contemporary Philippine society is filled with messages that advance American and Western elitism and the idea that Filipinos are second-class. The US still maintains a military presence in the Philippines. Skin-lightening remains one of the largest industries in the islands as the people try to live up to the American ideal. The construction of economic dependence in the 20th century continues the dark legacy of colonial oppression.

Today, Filipinos demonstrate uniquely high rates of mental health issues, such as suicide ideations and depression, but psychological research on Filipino and Fil-Am experiences remains sparse. Colonial mindsets have led to depression, anxiety, bitterness, and innercommunal conflict. Without significant efforts, these trends will continue.

Surrounded by Swords

There’s a Filipino riddle that goes, Isang magandang señora, libot na libot ng espada. Roughly translated, there is a beautiful lady surrounded by swords. For nearly half a millennia, the Philippines have been accosted on all sides and held under ruthless and dehumanizing oppression. Official colonialism has ended, but the swords remain.

The pressures to assimilate and forget the atrocities of our colonial past are powerful. Growing up, I did not hear any of these stories, neither from the American school system nor from my grandmother. It wasn’t until the summer of 2020 that I learned that my grandmother was an immigrant, that my great-grandfather was a sakada, or even heard his name: Alberto Subia.

These stories are not so much hidden as they are forgotten. Theologically speaking, we are purchasing salvation at the price of denial and minimizing sin. We are refusing that which makes us human by cutting ourselves off from our families, our histories, our cultures, and our lands. We are refusing to become the kind of people the Spirit intends by avoiding hard ethical questions with far reaching implications for God’s world and and its many inhabitants. We must think theologically of the swords.

As a mixed-heritage Fil-Am, I receive all sides of this history. The swords live within my family and within myself. Members of my family have benefited from colonial structures and members of my family have suffered the same. What does it mean to do theology from a place threatened by swords from within and without, haunted by the ghosts of colonizers and revolutionaries alike? The next two posts will engage this question by confronting Filipino Invisibility and suggesting Multi-Heritage reading humanity, community, and the New Heavens and New Earth.1

Continue reading with Part Three: The God Who Sees Us.

- Much of the information given above can be found in EJR David, Brown Skin, White Minds: Filipino-/American Postcolonial Psychology (Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, Inc., 2013); Luis H Francia, A History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos (New York: Abrams Press, 2014), ↩︎