(in)visible to Everyone but Me

Doing theology as an American-Made Mestizo, Pt 1

The following is the first part of a series reflecting on a Mixed-Heritage Filipino-American Identity in honor of Fil-Am Heritage Month. I will be discussing things like Filipino Invisibility, liminality and in-betweenness, tokenism, and the history of Filipino Diaspora. Some of the experiences will be common to radicalized communities, others will be particular to mixed-heritage persons, and others will be specific to me and my family. Ultimately, what I am building toward is a life-long struggle of theological reflection on mixed-heritage experience. Isang Bagsak.

“Ah, I knew there was something different in there!”

“Really? Nothing about you would have told me you’re Filipino.”

“You know, I could tell you weren’t just a normal white guy.”

“So do you, like, eat the food and stuff?”

“What part? How much?”

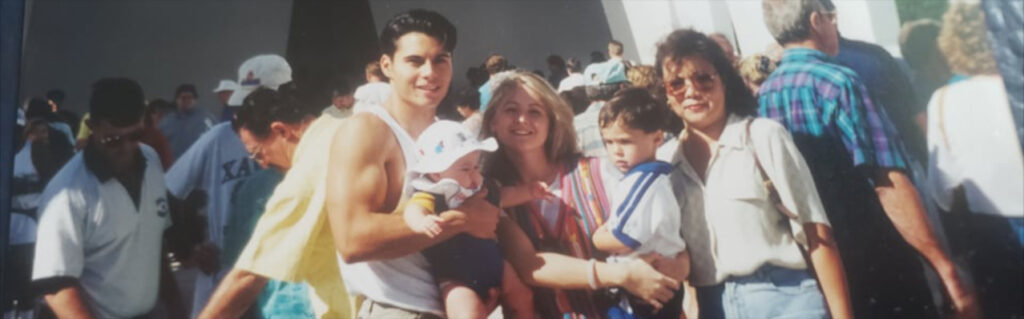

These questions, however innocent and genuine, often carry assumptions about what it means to meet the mark of ethnic credibility for mixed-heritage people—what it means to count as one thing or the other. You would not know it from my name and, depending on your own social location, you may not recognize it in my face, but I am the product of multiple immigrations. I inherit a complicated European lineage from my mother and, from my father, the stories and struggles of Filipino diaspora.

My great-grandfather was of the manong generation, the “imported ones” who worked Hawaiian sugar plantations during the explicit colonial period of US-Philippine military occupation. My grandmother was born in Ilocos Norte, but was brought to the United States at the age of seven to learn the necessary skills of assimilation, survival, and invisibly. These she passed on to her sons so that, in the span of a single generation, the islands were erased from our stories, our names, our meals, and our minds.

For me and my siblings, the race conversation is always confusing and often painful. In every space I enter, I feel the pressure to identify the right way and find myself seeking signals of permission from those around me to claim not only my identity but my story, my heritage, and my family. Who can I be with these people and whom do I have to leave behind as distant memory? My racial identity is never uncontested, to be determined by others who decide the parameters and validity of my upbringing.

invisibility

Given the contested nature of a mixed-heritage identity, I find a certain level of comfort in spaces where my “Filipino-ness” is rendered invisible. But any comfort afforded by the calm of being unseen is purchased with self-bifurcation, comfort at the price of fragmentation.

The comfort of invisibility is often disrupted by explicit racism that, from time to time too many, has been directed toward my skin, my eyes, and my family, or burdened by jokes and tokenism among true friends. Comfort sits uneasy in the rare-charted complexities of raising two girls who inherit my stories and yet will never be considered Filipina. It is confronted by the constant and unrelenting reality of Filipino Invisibility – that in nearly every space where Asian or Asian American stories and experiences are considered, Filipinos (until very recently the second-largest Asian American subgroup in the U.S.) are forgotten, overlooked, and otherwise not invited to the table.

In these instances, I am left asking whether I am Filipino enough—whether I am enough of my father’s son—for this group of people to speak up for my invisibility and the invisibility of my family. Yet I remain confronted by the fact that I cannot build relationships on pieces of myself. As a father, I cannot raise my daughters in a way that erases my grandparents, my father, and the stories that brought us here. As a theologian, I cannot do theology honestly by hiding parts of who I am from myself, from Scripture, or from the Lord. Without honest naming of self and world, any constructive and healthy theology is impossible.

Self-Naming and Theologizing

All of theology is contextual and demands honest self-naming. No theology is constructed, communicated, or received in a vacuum. Theology that pretends objectivity and neutrality only hides itself from its own biases and presuppositions, preaching absolutes out of contingencies or whims. The world knows no shortage of damage wrought by such theologies.

Maria Root, a multi-heritage Filipina and clinical psychologist, points out that self-naming—one of the breakthroughs of racial empowerment—takes longer to reach the multi heritage community.1 Like many mixed-heritage persons, I carry with me the sense that I am both-and-neither, inhabiting a liminality between multiple social locations. The mono-racial and monocultural logics that undergirds much of society and our social imaginations makes it difficult to identify in any way integral to our past, which is only relevant to the extent that others allow, and we look for permission to validate ourselves.

So, one of the first steps in doing theology from a mixed-heritage is naming that experience so that it can be held honestly within the biblical narrative and shed light on theological tensions. This will be the task of the next several posts in this series on doing theology as an American-Made Mestizo.

Continue to reading Part Two: Surrounded by Swords.

- Maria P. P. Root, “Within, Between, and Beyond Race,” in Racially Mixed People in America, ed. Maria P. P. Root, 3-11 (Newbury Park: SAGE Publications, Inc., 1992), 7. ↩︎

Great piece my friend. I never knew there was Philipino in you. I fully agree with “All of theology is contextual and demands honest self-naming. No theology is constructed, communicated, or received in a vacuum. Theology that pretends objectivity and neutrality only hides itself from its own biases and presuppositions, preaching absolutes out of contingencies or whims. The world knows no shortage of damage wrought by such theologies.”

Thank you…