Fellowship with Darkness: On whether Christians can watch horror movies

Do not be yoked together with unbelievers. For what do righteousness and wickedness have in common? Or what fellowship can light have with darkness?

October 2013, sitting around the lunch table, some friends and I decided to hit up some local haunted houses. We left an open invite to any who wanted to join us. A few took us up on our offer, but I’ll always remember one specific response. “No, I don’t do that sort of thing,” she said. “What fellowship can darkness have with light?” Despite the horrible twisting of 2 Corinthians 6:14 so wildly out of context, many Christians are reticent to engage with horror.

Another October some years later, I was working in a faith-based thrift store. The background music started playing “Spooky, Scary Skeletons”, a children’s Halloween song about misunderstood skeletons wanting to socialize. One customer, bothered by such unwholesome lyrics, asked us to change it to something more holy.

“Christians don’t listen to stuff like this.”

Mike Duran published an article with The Gospel Coalition in 2018 titled, “Why the Popularity of Horror Movies Might Encourage Christians”. He basically argues that the ongoing appeal of the horror genre should interest the church for what it tells us about ourselves and the world. The responses were telling.

One commenter accused Duran of justifying his own “creepy indulgence”. Several added their disappointment that TGC would publish such an article. Many commenters charged horror with opening a doorway to hell and giving Satan a foothold in the lives of viewers. But the most revealing comment was also one of the shortest: “I don’t watch evil movies”.

There are those who don’t consume horror stories simply because they don’t like the stimulation or don’t like contemplating horrific things. This is fine and fair and, as a rule, I don’t try to convince people to watch horror if it makes them genuinely uncomfortable. However, individual discomfort often twists into an assumption that horror affects everyone the same way–or should affect everyone the same way– with a deep suspicion towards those who claim otherwise.

Consuming horror is considered unwise at best and perhaps even sinful by many Christians. This post looks at two of the main objections to the horror genre and asks the question, can Christians watch horror movies?

Objection One: The Devil’s Foothold

There is a general fear among Christian circles that watching horror movies with supernatural influences might “give the devil a foothold” (Eph. 4:27). This oft cited verse is actually about resolving our anger (v. 26), but could include a seriousness about lying (v. 25), stealing (v. 28), discouragement and derision (v. 29), and bitterness or malice (v. 31). Conspicuously absent is any prohibition against watching scary movies. But the avoidance is not a matter of exegesis, so I digress.

At large, Christians don’t actually draw the line at supernatural content. Many Christians love C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia, which includes witches, werewolves, and wraiths. Many Christians devour the works of JRR Tolkien, whose main villain is a necromancer, include ghosts and even demons, and depict swamps filled to the brim with corpses. Of course, in these books and films, the dark supernatural forces are evil and are defeated by the protagonists, highlighting the triumph of good over evil.

This is something they share with most horror media.

Ironically, the films that seem to be the easiest targets (like The Exorcist or The Conjuring) are also accused of being Christian propaganda for the way that they depict evil overcome by the power of faith in God. Far from depicting the triumph of evil, horror often depicts the defeat of evil by the forces of goodness and faith.

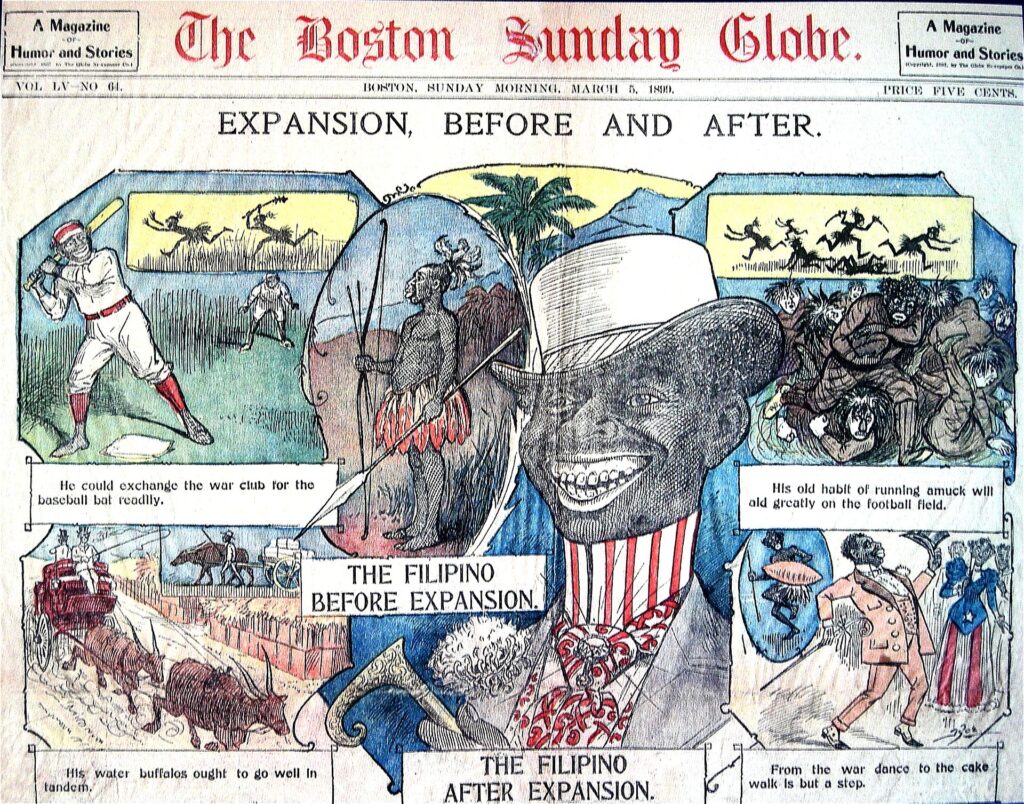

If Satan is given an automatic foothold while watching horror films that portray his own defeat by the power of Christ, what about other movies that display human suffering? Will watching Schindler’s List give Satan a foothold? Or was the devil not at Auschwitz? I wonder, too, if Satan would enjoy watching The Three Stooges. After all, the long-running comedy treats pain – a product of the curse of sin and rebellion against God – as humorous. One wonders if Christians believe that sin is a laughing matter.

The point is neither that slapstick comedy is sinful nor that Lucifer watches Saving Private Ryan with a smile, but that the onscreen depictions of evil do not disqualify a film, let alone a whole genre. Christians should avoid darkness, but laughing when someone stubs their toe does not count as fellowship, and neither does cheering when Laurie Strode escapes Michael Meyers.

Objection Two: Too Much Blood

While there are movies that feature almost no blood (The Blair Witch Project, The Others), I won’t argue that horror hasn’t poured out rivers of corn syrup for those in search of graphic violence. Movies like Sweeney Todd, Hellraiser, and Evil Dead come to mind as special offenders. And of course, there’s always that one scene from Carrie.

In 2017, Tony Reinke wrote for Desiring God pondering the “wild success of horror movies in our culture, especially the most graphic and bloody ones”. He was talking about Andy Muschietti’s It: Chapter One, released earlier that same year. Despite no plans of ever seeing the film, Reinke was encouraging Christians to steer clear.

It certainly contains some violence. The movie opens with a sewer-dwelling clown biting off poor Georgie’s arm. In another scene, blood erupts through a bathroom drain, covering the walls and ceiling. However, considering the film’s terrifying premise, the body count is actually quite low: four. Compare this to the critically-acclaimed Saving Private Ryan, which boasts onscreen deaths upwards of 250.

When you really get into it, horror films aren’t actually as gory as many assume. Between 1998 and 2007 (the heyday of movies like Saw), the total average of onscreen gore per film was less than four minutes. Most of this was “passive gore”, like blood splatters and severed limbs. The average horror film actually only spends 50 seconds actively depicting bodily violation. Compare again to Saving Private Ryan, whose opening scene boats a famous 25 minutes of photorealistic slaughter.1

Christians carry with them a fear that watching bloody movies will make violent people. The so-called torture porns (or “gorno” flicks) were supposed to lead to a proliferation of Jigsaw-like serial killers, but the fears have proven unfounded. The world is still waiting to see the rise in horror movie copycats, just as it is still waiting for the promised Satanists and psychopaths nursed on Dungeons & Dragons.

But even if violent films increased aggressive feelings (and there is scant proof of that), why should horror be the only suspect? What about those movies that portray violence in slick, beautiful ways with no lasting consequences for the victims? Horror – unlike John Wick, Tom and Jerry, and every addition to the Marvel Cinematic Universe – depicts violence in all its grisly horror. It admits that it is evil.

Moderation and Grace

Christian filmmaker Scott Derickson once said that some people shouldn’t watch horror films, “and I’m alright with that.” Horror isn’t for everybody, but every genre has its concerns.

Comedy has a knack for being too irreverent, unnecessarily offensive, blasphemous, dehumanizing, and sometimes just gross. Tragedies potentially increase depressive feelings in those who struggle with clinical depression, but Christians are not calling for the mass boycott of such films. Action movies, too, can be mere stimulus, distraction, and revenge-fetishism.

The key is moderation, knowing your own threshold, and healthy portions of grace for those whose threshold is different than your own.

For some people, horror movies are not healthy. If horror spikes your anxiety, floods you with intrusive thoughts, or otherwise makes it difficult for you to function, it may not be wise for you to imbibe. If watching a slasher makes you want to cut open your neighbor, maybe try counseling. Or if watching the latest Marvel film makes you want to leap out of a seventh story window, consider a parachute, just in case.

Otherwise, if you simply reject horror on would-be theological, moral, or otherwise spiritual grounds, I will ask you to reconsider. Everyone – and I do mean everyone – has a sweet spot for fear, whether that’s horror movies, roller coasters, or surprise parties. If you think about it long enough, there are probably movies that you’ve enjoyed that others find scary or troubling, at least in moments. Perhaps you could take a closer look at the genre, albeit with trepidation. You may find that while horror, like Scripture, is filled with violence and blood and all manner of scary things, it can also offer tremendous hope in dark places and a way of understanding the horrors in our world.

- Blair Davis and Kial Natale, “The Pound of Flesh Which I Demand”, in American Horror Film: The Genre at the Turn of the Millennium, ed. Steffen Hantke (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010), 35-56. ↩︎