Returning Forward

Doing Theology as an American-Made Mestizo, Pt. 4

The following is the third part of a series reflecting on a Mixed-Heritage Filipino-American Identity in honor of Fil-Am Heritage Month. You can find part one here.

I will be discussing things like Filipino Invisibility, liminality and in-betweenness, tokenism, and the history of Filipino Diaspora. Some of the experiences will be common to radicalized communities, others will be particular to mixed-heritage persons, and others will be specific to me and my family. Ultimately, what I am building toward is a life-long struggle of theological reflection on mixed-heritage experience. Isang Bagsak.

“Just make sure not to leverage your ethnicity too much.”

I’ve heard this sentiment a few times in academic spaces, the assumption being that I’m not Filipino enough to talk about my experience as a Fil-Am and that, in doing so, I’m really just chasing down diversity points. Enough is a big word in the mixed-heritage conversation.

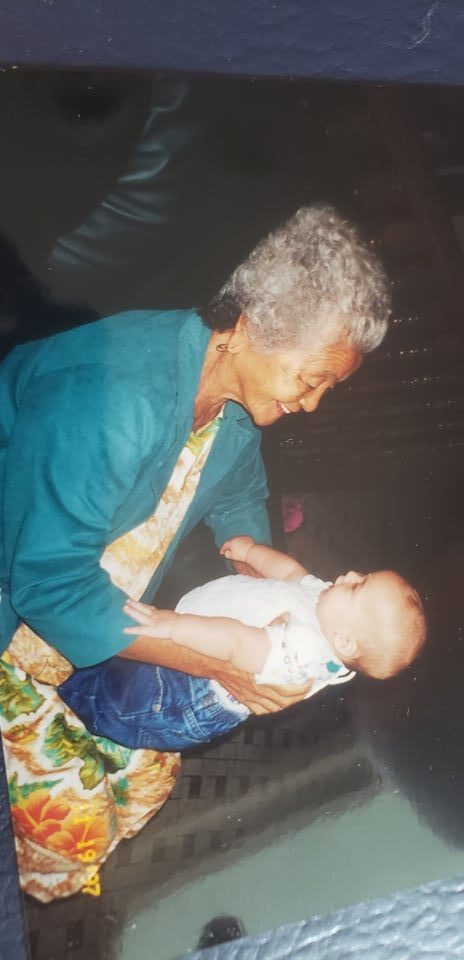

Am I Filipino enough to talk about my sakada grandfather or my immigrant grandmother? Have I experienced enough racism, tokenism, or microaggressions to admit that it’s hurtful? Have I heard enough jokes about my eyes, been confused for Latino enough times, or had enough people ask me what I think about Manny Pacquiao to consider myself Filipino American? And who gets to decide, anyway?

Mixed-heritage people experience pressure from all sides, within and without, to identify the right way for any given context. The question of legitimate membership in a group always feels contested. We are both-and-neither, betwixt and between, and not quite this or that.

As such, it is both comforting and chaotic to be in places where our non-white ethnicity is expressed and celebrated. If I go to a Fil-Am Heritage Month celebration at my seminary—to eat my childhood food and hear other Fil-Am stories—will I be accepted, or will I be accused of leveraging my heritage to assuage some underlying white-guilt?

I am haunted by the question of belonging.

To Be Kapwa

Many have followed Virgilio Enriquez, founder of Sikolohiyang Pilipino (the Filipino psychology movement), in identifying kapwa as the foundational concept for Filipino worldview.1 While sometimes rendered in English as simply “others” or “both”, kapwa more the unity of the self and others, together.2 “Without kapwa,” says Enriquez, “one ceases to be Filipino… One also ceases to be human.”3

The term, like many indigenous terms, resists one-to-one correspondence with English terms, but Jeremiah Reyes offers a helpful starting place. Instead of translating kapwa as “community” or “fellowship”, which still foregrounds the modern concept of individual selves, Reyes translates kapwa as “together with the person”. For Reyes, “if you want to define kapwa… there is no ‘self'” in the modern sense.4

This doesn’t mean there are no individuals. Instead, individuals receive identity from the group rather than the group receiving identity from the individuals. In the framework of Western individualism, the “self” is the starting point for membership in a community of other “selves” that interact together. In kapwa, together “comes first before you break it apart into separate ‘selves’.”5 Relationality is not a choice, decision, or preference of individuals, it is a web within which individuals are together.

Furthermore, we mustn’t understand kapwa as the Filipino version of “others-centeredness”. Kapwa does not set the other up over the self any more than the self is set up over the other. They are both, to accept Reyes’s definition, together, so that collective identity is ontologically prior to individual identity.

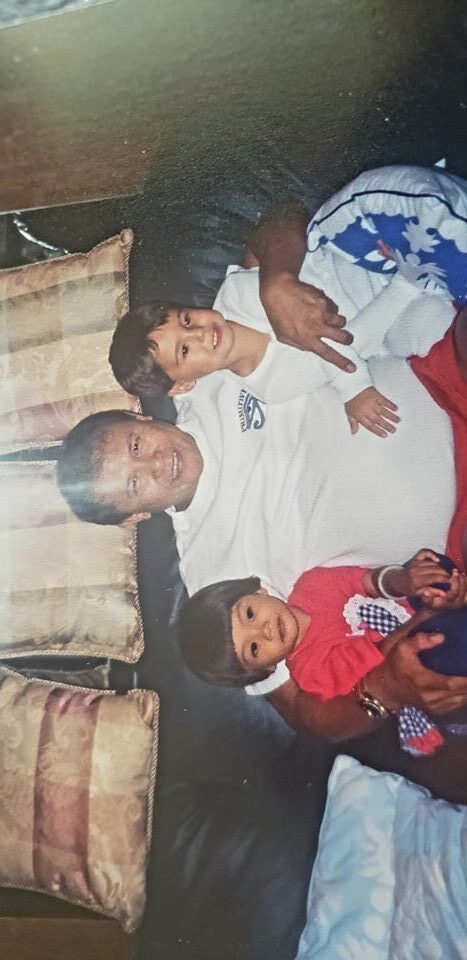

More could be said on the psychological logic of kapwa. Suffice to say, the Filipino concept of kapwa demands the communal identity and solidarity of all Filipinos, including Fil-Ams. Being together—in community—is what makes any of us human. If one of us is hurting, we all hurt in kapwa. If one is dehumanized, we are all dehumanized. And yet, Fil-Ams do not always experience kapwa.

Reclaiming Kapwa with Tainted Blood

The denials and reclamations of kapwa have added layers for mixed-heritage peoples. It is, as one Filipina-American put it, to feel both ashamed and guilty of being mixed, feel part-oppressed and part-oppressor.6

In seeking for permission to identify—to claim their families and their stories—mixed-heritage persons are seeking humanity. We were not meant to be fragmented, invisible, or ambiguously liminal. We are meant to be kapwa—together.

For Fil-Ams, reclaiming kapwa is an act of resisting colonialism and an act of liberation. As a mixed-heritage Fil-Am, my connection to kapwa is always contngent and mediated through my experience with others—whether white or brown—to whom I look for permission to identify and voice various pieces of my identity. My kapwa is up for debate and deliberation in the communities I inhabit, accepted or rejected on their terms. With my kababayan, I am invisible to dominant cultures and Asian American communities alike. Among my kababayan, I can still feel invisible. Because kapwa cannot be complete while others are excluded, my kababayan are not yet kapwa until I am kapwa with them.

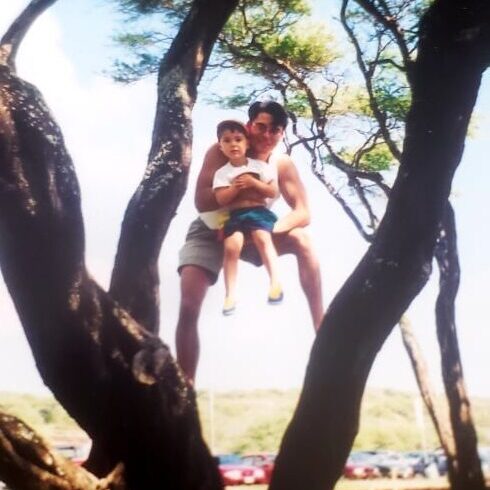

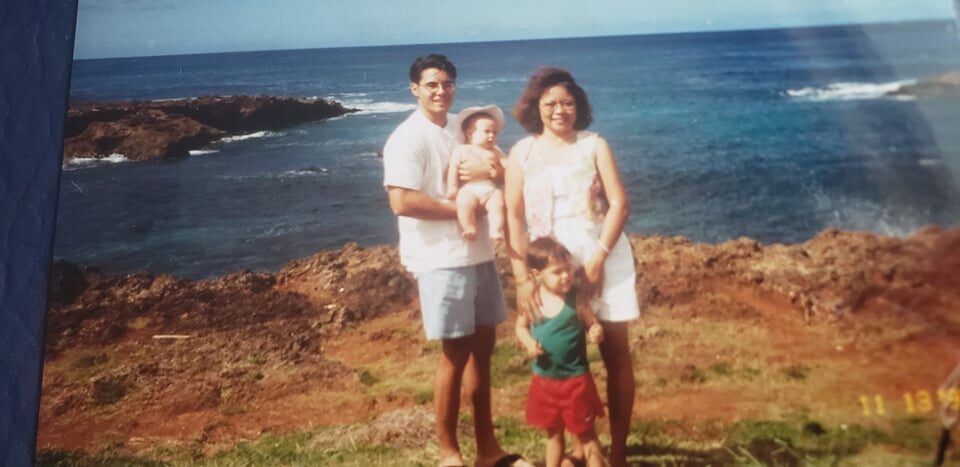

Yet, I am the product and recipient of multiple immigrations, multiple diasporas, multiple histories, and multiple cultures. In order to reclaim kapwa with tainted blood, I cannot restore a shared identity with only Fil-Ams or other Filipinos. I remain walang kapwa (without humanity) until my together includes my father and my mother—their families, their histories, and their peoples.

Mixed-heritage people defy monoracial and monocultural logics, but we also present unique opportunities for reconciliation and reimagining a multi-heritage world. Kapwa has the potential to unite Filipinos and Fil-Ams, including mixed-heritage Fil-Ams, and because we must be kapwa with all of ourselves, it connects groups which would otherwise remain without the other.

Returning Forward: Mixed-Heritage Revelation 22

Filipino Invisibility rubs salt into colonial wounds and contributes to the loss of kapwa and the difficulty of reclaiming kapwa with our kababayan, with fellow Asian Americans, with the whole community of creation (kapwa-nilalang). Because we are all meant to be kapwa in the communal Image of God, Filipino invisibility is human invisibility. In failing to see us, others fail to see themselves.

As a mixed-heritage Fil-Am, this erasure has meant that there are parts of my humanity that have too long gone unseen by my friends, my family, and myself. But we are not invisible to God. The Spirit of God is moving unseen in our unseen midst as a healer who is restoring our kapwa in his restoration of all of creation. God will make all things kapwa when heaven meets earth and Christ makes his dwelling here.

It is said that on that day the rulers of the earth will bring their glory into the heavenly city. Out of invisibility, Fil-Ams will bring our history, our culture, our heritage, and our gifts to bear on the new creation.

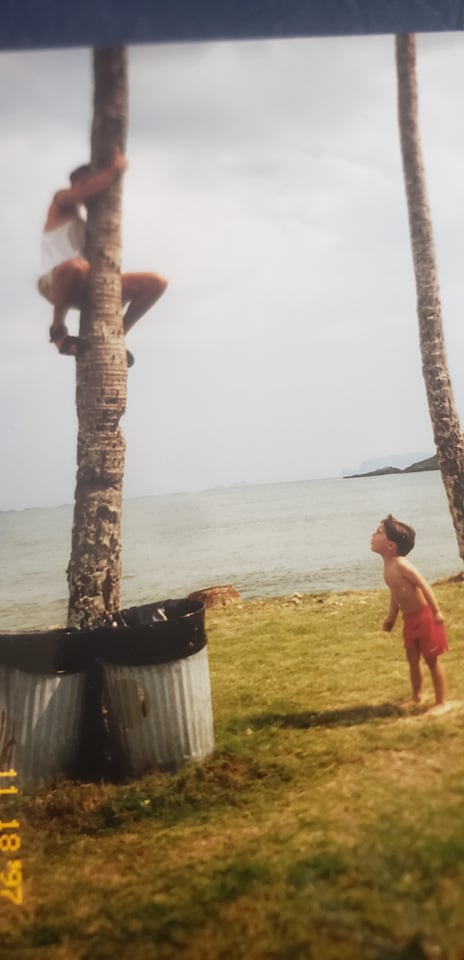

As a mixed-heritage Fil-Am, I cannot “go back” to where I’m from. I live on stolen land, born to a mother from Europe and a father from the Philippines, and I am not from any of them. I can only be present where/with who I am in kapwa and move forward towards the new creation to which God is calling us. From my past, I carry with me a plurality of stories and cultures. When I enter the heavenly city, I will leave none of them and none of myself behind when I enter through the gates.

Walang makakatigil. Isang bagsak.

- Virgilio G. Enriquez, “Kapwa: A Core Concept in Filipino Social Psychology,” in Philippine Worldview, ed. Virgilio G. Enriquez (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1986); see also E. J. R. David, Brown Skin, White Minds: Filipino-/ American Postcolonial Psychology (Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, Inc., 2013). ↩︎

- Enriquez, “Kapwa”, 11. ↩︎

- Virgilio G. Enriquez, From Colonial to Liberation Psychology: The Philippine Experience (Manila: De La Salle University Press, 1994), 63. ↩︎

- Jeremiah Reyes, “Loób and Kapwa: An Introduction to a Filipino Virtue Ethics,” Asian Philosophy 25, no.2 (2015): 156. ↩︎

- Reyes, “Loób and Kapwa”, 156. ↩︎

- David, Brown Skins, White Minds, 73. ↩︎